Born in Sydney Australia to Jewish faith parents, who survived the Holocaust and fled Europe in 1954, I have naturally been drawn to European 20th Century history. Especially to the study of WW1 and WW2. It was this interest that inspired me to create a body of photographic work, that I called Stories from the Holocaust.

This exhibition, travelled the world in 2019-2020 and featured 50 images of the personal items that were left behind by the victims of the Nazi’s, in two concentration camps. The all women’s and children’s concentration camp of Ravensbrück and the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen. Both of these camps are in Germany and only 90 minutes by car from the centre of Berlin.

I was granted privileged and exclusive access to the closed archives of the memorials Sachsenhausen and Ravensbruck to photograph the camp victim’s personal artifacts that have never been seen before. While at the same time, using the original camp SS garrison records, I was able trace back each item to their original owner and consequently to learn their fate.

Working with world renowned German Historian Dr Robert Sommer, we were granted privileged access to the archives that included artifacts found at the camps after liberation, or were donated by the survivor or their families. I like to think that we have been able to rescue the voices of the dead with our images and with our historically based texts, we were able to give the silent an opportunity to speak to us once again with collective voices.

I am a minimalist when it comes to my photographic work and the simplicity of each image is intentional. The simpler the image is to me, the better i can understand what that photograph is trying to say to us. I like to think of each image as a portrait of that person. A person who is no longer alive, but can still speak to us via the medium and language of photography. It is my sincere hope that each image speaks to you, makes you think about what you are seeing, makes an emotional connection with you and perhaps engages with you enough to warrant you to share what you have seen, with other people.

I like to think that each image gives us a look at who that person was. What can these images tell us about that person? Who were they, where did the live, what towns or cities in Europe did they come from? And what can these images tell us about life, death and survival in the most brutal of environments? The poignant imagery and the linked historical researched texts, share both the horrors and hope within the Nazi concentration camps. Somehow giving each image its own context and ‘life’.

I currently have my studio in Sydney, Australia and have completed recent works with The Centre of Disease Control C.D.C in Atlanta and working with survivors of the Twin Towers September 11 terror attacks in New York. Also, my most recent body of work, photographing the men and women who served in the Australian Defense Force, in the- atres of war in Afghanistan. This work was acquired by The Australian War Memorial in Canberra – our capital city.

Violette Rouge (née Lecoq) was a member of the French resistance movement. Working as a nurse she helped more than 80 French soldiers escaping from Nazi-occupied France. In 1942 she was arrested and held in isolation before being sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1943, where she worked in the Tuberculosis ward of the infirmary. She witnessed the murder of many women who were no longer fit to work.

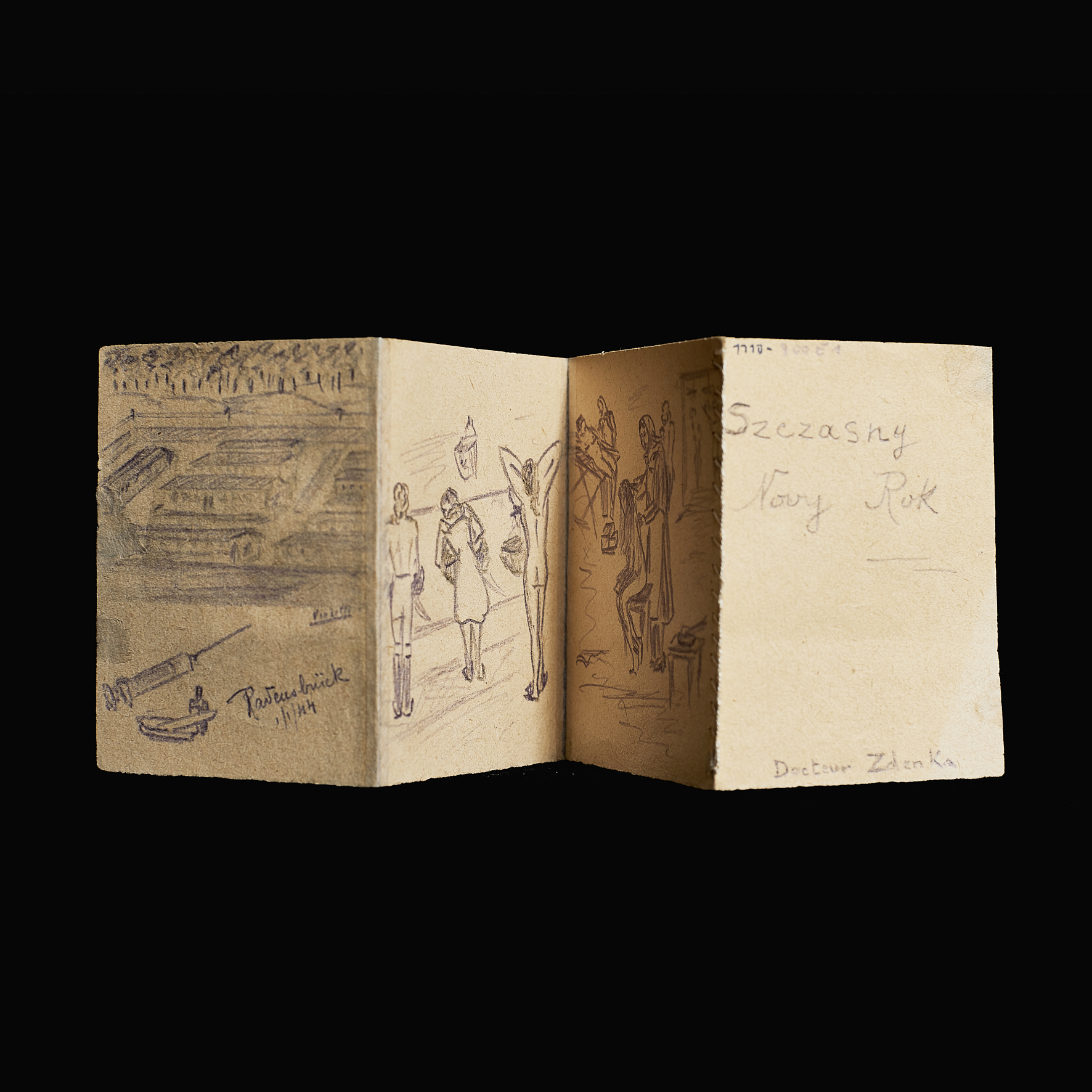

Violette created this leporello (folded drawing) and gave it as New Year’s Day present to Zdena Nedvedová, a Czech prisoner and doctor respected by fellow prisoners for her ethical practices. Her drawings show scenes from everyday life in the camp infirmary, such as nurses taking care of patients or women washing themselves.

Of particular interest is the drawing of an SS-doctor in uniform examining naked women. According to Violette, the physician was Dr. Percival Treite, a gynecologist who carried out sterilization experiments and selected women for killing. It’s possible that such a selection is shown in the drawing.

In 1947, Dr. Treite was found guilty of crimes against humanity by a British court and sentenced to death, but he committed suicide before his execution.

Original object size: 2.7’’ x 3.8’’ (6.9 cm x 9.7 cm)

This teddy bear belonged to an unknown Sinto boy, mur- dered at the Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1944. He arrived there with adults and many other children off a gypsy transport. Walking down the main camp street the children, unable to keep pace with the adults, were often beaten by SS guards.

The young Sinto boy accidently dropped his teddy bear. As he bent to pick it up, a guard hit the boy’s head with a rifle butt, killing him.

The German political prisoner and resistance fighter, Anni Sindermann witnessed that scene. She secretly picked up the teddy bear and hid it for the entire time of her imprisonment in Ravensbrück. When sent on a death march in 1945, she took the teddy bear with her.

After her liberation and for the rest of her life, Anni Sindermann repeatedly told the story of this little boy and his teddy bear, to keep his memory alive.

Original object size: 5.5’’ x 1.2’’ (14.0 cm x 3.0 cm)

Occasionally women arrived pregnant at concentration camps. Any babies born in Ravensbrück had a very low life expectancy, as there was rarely enough food and milk in the camp to sustain the life of a newborn child. Because of this shortage, prisoner doctors, who had been tirelessly engaged to help sick prisoners, found themselves in a dilemma. They had to prioritize milk for babies who had a realistic chance of surviving.

Sylvia Elisabeth was born in 1944 in Ravensbrück. Her mother, Conny van Otten-Snijder, had been arrested because of her participation in the Dutch resistance movement. Sylvia Elisabeth was a child born early, at seven months gestation. Prisoners took a beautiful white baby dress out of the stock room, smuggled it into the camp infirmary and dressed the baby with it.

Sylvia Elisabeth lived for just four weeks.

Her mother, Conny van Otten-Snijder, was liberated from Mauthausen concentration camp in July 1945 and returned to her home in Den Haag. After the war Conny gave birth to another girl, Miriam. When her mother passed away in 2011, Miriam donated the dress of her older sister to the Ravensbrück memorial.

Original object size: 11.3’’ 11.8’’ (28.6 cm x 30.0 cm)

In concentration camps music was often used to torture prisoners. The SS guards forced prisoners to walk to Ger- man marching songs or endlessly sing German folk songs. Music also provided prisoners with a comforting distraction from the never-ending suffering in the camp. Sometimes prisoners played music during their illegal gatherings. Occasionally the SS would allow prisoners to play music for special events.

Charlotte Müller was a German resistance fighter who was brought to Ravensbrück in May 1942. In the camp she worked in the “Klempner-Kommando” (the plumber squad). This meant she could move around within the camp and as such she became an important part of the camp resistance movement.

In December 1944, Charlotte Müller convinced the SS to give her special permission to organize a Christmas concert for prisoners at Ravensbrück. The SS gave her and two of her comrades musical instruments, that had been stolen from other prisoners at their arrival: an accordion, a guitar and a violin.

The three formed a group and collected international Christmas songs from other inmates in the camp and practiced them. They had to be careful not to play too well, fearing the SS would order them to play during their drink- ing bouts.

Original Object Size: 3.5’’ x 8.7’’ x 23.2’’ (9.0 cm x 22.0 cm x 59.0 cm)

Life in concentration camps comprised of grueling, slave labor. Leisure time was short and any activity that helped prisoners escape from the hell of the camp was precious.

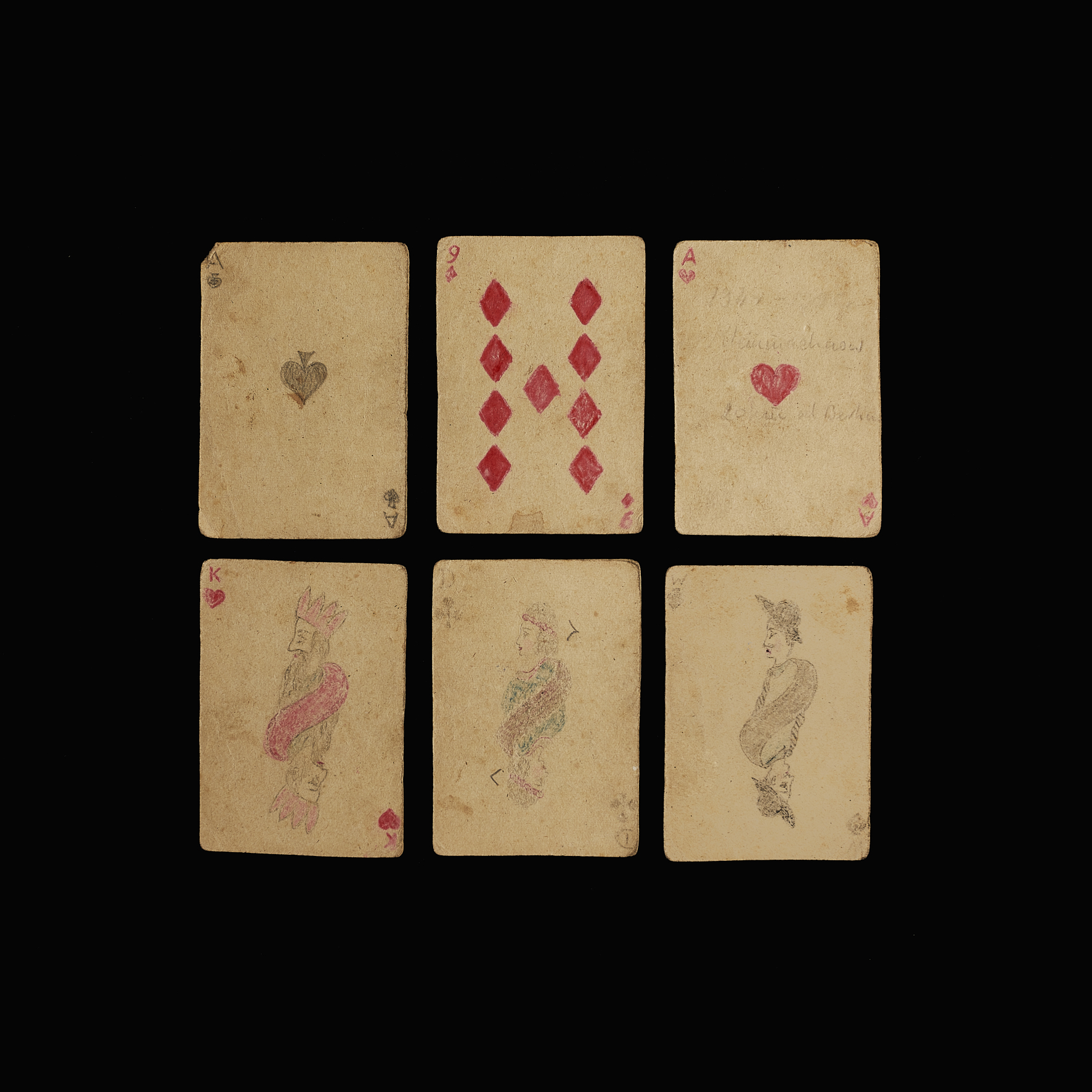

This deck of 24 cards was cut from cardboard used at the Dreilinden Maschinenbau, a factory that was part of the Bosch Corporation, where Polish women were forced to work in rotating 12 hour shifts under the watchful eye of the SS soldiers. Since the paper was stolen from the factory, owning this deck of cards was would be considered sabotage. The punishment would be death. These cards are handmade and drawn with crayons. There is a Polish pencil writing on the Ace of Hearts. “1944-1945 w Kleinmachnow 20 min od Berlin.”

The deck of cards was owned by Jolanta Sikorska, a Polish woman most likely arrested by the Nazis after the Warsaw uprising. In 1944, she was brought to Ravens- brück and then transferred to the Sachsenhausen subcamp Kleinmachnow, just 20 minutes away from the Reich capital. There she stayed, as noted on the card, until 1945. Weak and starving, the prisoners of Kleinmachnow were then sent back to Sachsenhausen and forced on a death march towards the town of Schwerin. Weak and starving, many women died along the way. Jolanta Sikorska’s fate is unknown.

Original object size: approx. 3.5’’ x 2.3’’ (8.9 cm x 5.9 cm)

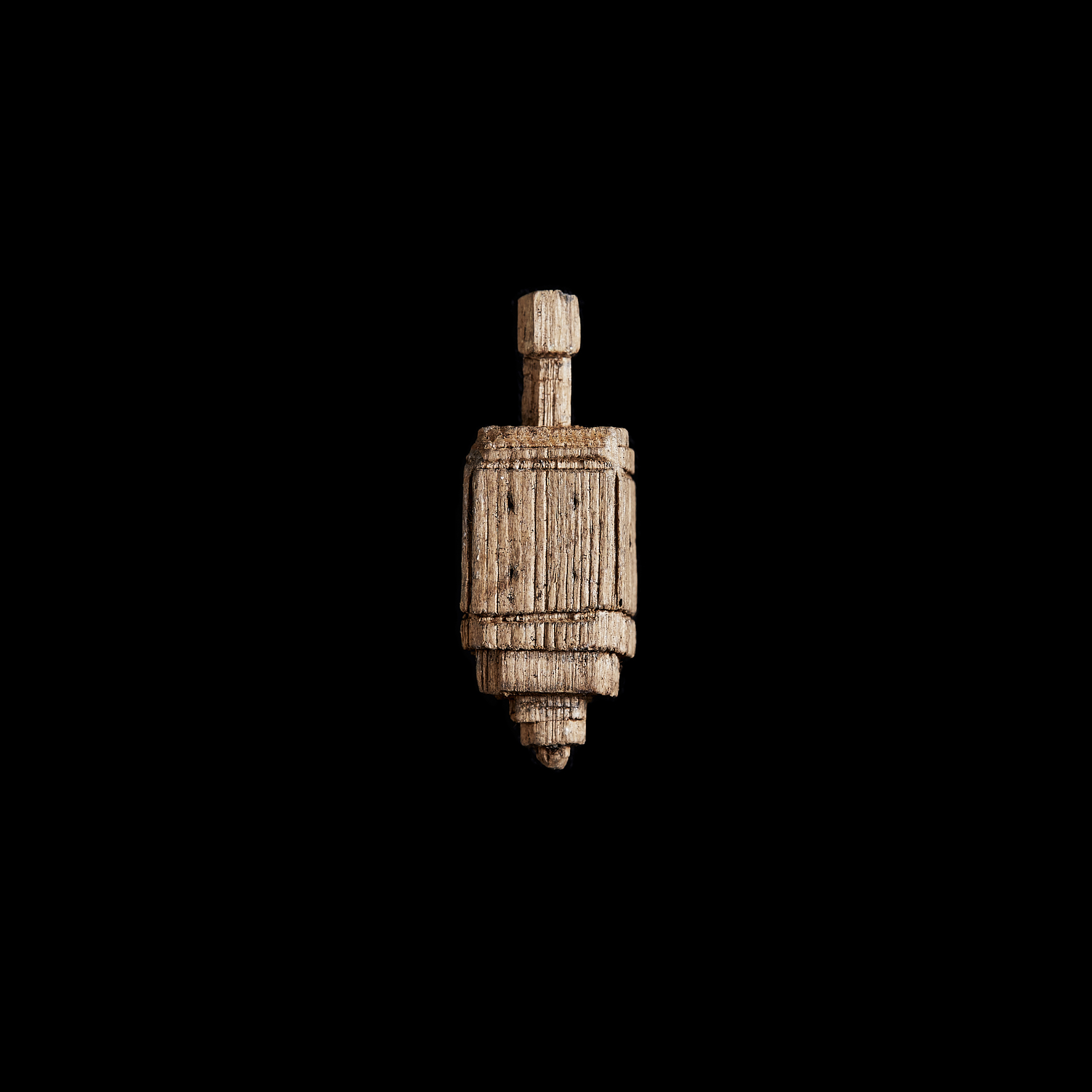

This dreidel (a Jewish spinning top) is from the Lieberose concentration camp; a subcamp of Sachsenhausen located 100 kilometers southeast of Berlin. In 1944, Lieberose became the biggest concentration camp for Jews within the German Reich territory – Auschwitz was not located within the borders of the German Reich. It’s estimated 10,000 Jews were imprisoned there, but less than 400 survived.

The dreidel was found in a mass tomb. Next to this dreidel, a wooden box and other wooden figures from a chess-board were also found. Carved into the lid of the box is a Star of David with the Hungarian text “Elmek Lieberose”, translating to ”memory of Lieberose”. The box

contained two prisoner serial numbers. According to those, the owner of the box and the dreidel can be identified as either of these Hungarian Jews: Jakob Senger or Zoltan K.

Jakob and Zoltan were deported to Lieberose in 1944 for slave labor. When they could no longer work due to exhaustion, the SS sent them back to Auschwitz to be killed in a gas chamber. Jakob or Zoltan probably gave the dreidel to a comrade at Lieberose, before being sent back to Aus- chwitz. Later in February 1945, that comrade was shot and his body dumped in the mass grave along with this dreidel.

Original object size: 1.1’’ x 0.3’’ x 0.3’’ (2.9cm x 0.8cm x 0.8cm)

In the early 1940s, most concentration camps were over- crowded. Basic resources such as space and food were very limited. The SS garrison overcame that by reducing the number of prisoners.

SS officers and doctors frequently selected prisoners they deemed unfit to work – often disabled, sick or prisoners weak from malnutrition. Deemed to have no right to live, they were killed. Sometimes by being sent offsite to exter- mination camps equipped with gas chambers.

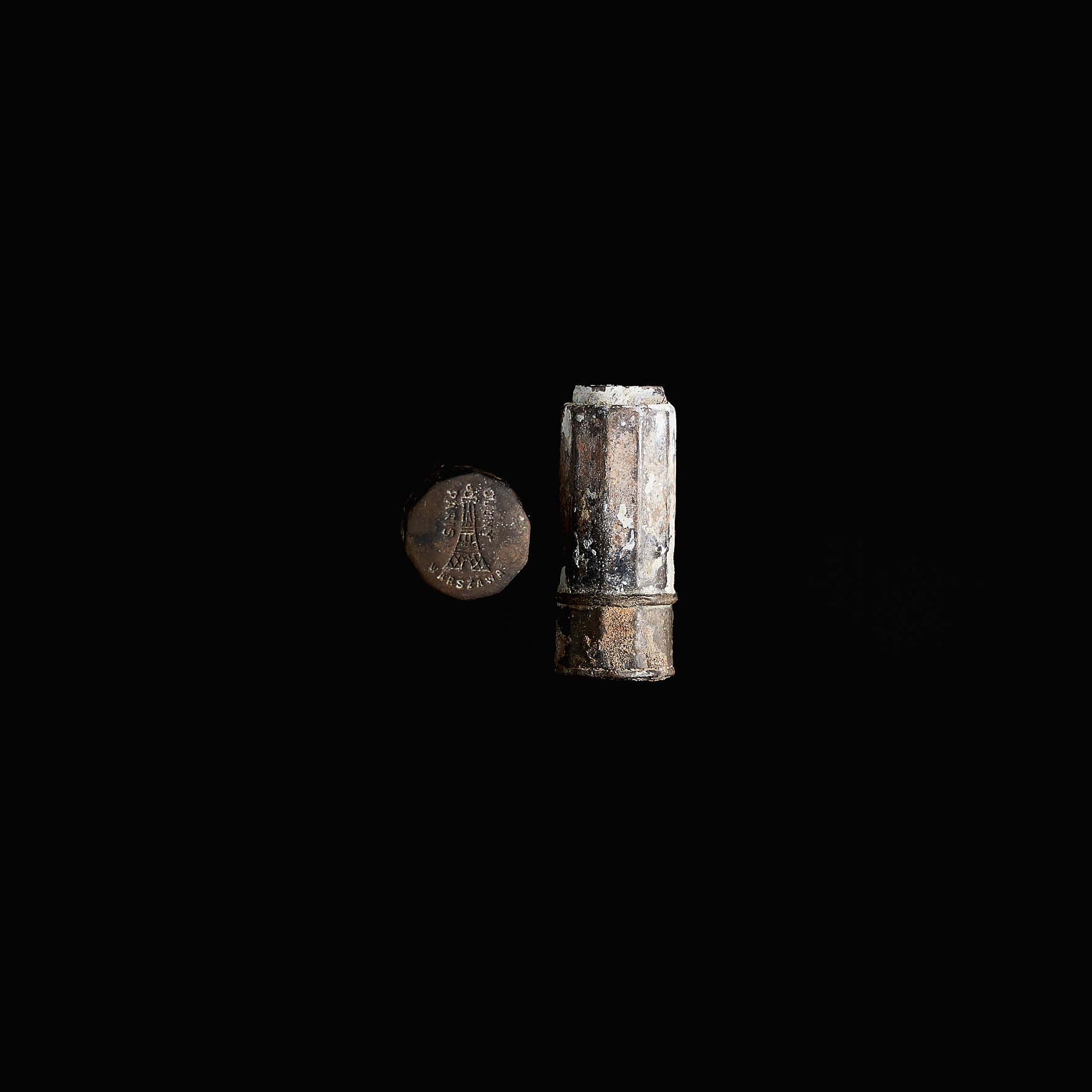

In the women’s concentration camp of Ravensbrück the preservation of a healthy female appearance became essential. Women tried to rouge their faces with red beads or stolen cosmetics to look healthier. Older women used soot to dye their hair. Such makeup could determine whether they lived or died.

Soviet soldiers found this lipstick on the Ravensbrück camp site in 1985. On the lid the Eiffel Tower is shown and the cities of Paris, Cluny and Warszawa (Warsaw) are written around it. In Ravensbrück, it was worth a fortune.

Original object size: height 1.6’’ (4 cm); diameter 0.6’’ (1.6 cm)

Nazis deported people to camps they considered political enemies, such as those with socialist or communist beliefs. These prisoners often brought their political fights with them. They knew that survival in Nazi concentration camps meant finding the courage to fight for one’s life. But they didn’t do it alone.

Despite coming from different countries and speaking different languages, prisoners often supported each other with food and protection, as well as through clandestine political congregations that strengthened their moral resolve against their captors. They held gatherings that created social communities, provided political education and hope for their comrades.

It wasn’t uncommon for prisoners to work together, smuggling items into the camp that continued to give them a purpose – even in the bleakest of times.

Through a secret compartment in the sole of her shoe, the French resistance fighter Martha Desrumeaux, was able to smuggle part of the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union into Ravensbrück concentration camp. Her comrades, Suzanne Cage and Georgette Cadras, managed to get the other two sections into the camp.

Once there, they used the book during clandestine meet- ings of their political resistance group, and as part of their plight for continued political education.

Original object size: 9.4‘’ x 4.5’’ (24.0 cm x 11.5 cm)